Investigating Proto-Illyrian migrations in Bronze Age Greece: J-L283 from Mygdalia, Peloponnese

by Arbër Ukgjini

Ancient Greece was a melting pot where many different migrations shaped its history. In the classical period, the high culture of the Aegean melting pot was characterized by ancient Greek as its prestige language and its homogenizing attribute.

Greece’s long and ever-changing demographic landscape was well known to ancient Greek authors. According to Strabo:

Now Hecataeus of Miletus says of the Peloponnesus that before the time of the Greeks it was inhabited by barbarians. Yet one might say that in the ancient times the whole of Greece was a settlement of barbarians, if one reasons from the traditions themselves: Pelops brought over peoples from Phrygia to the Peloponnesus that received its name from him; and Danaüs from Egypt; whereas the Dryopes, the Caucones, the Pelasgi, the Leleges, and other such peoples, apportioned among themselves the parts that are inside the isthmus—and also the parts outside, for Attica was once held by the Thracians who came with Eumolpus, Daulis in Phocis by Tereus, Cadmeia by the Phoenicians who came with Cadmus, and Boeotia itself by the Aones and Temmices and Hyantes. According to Pindar, there was a time when the Boeotian tribe was called “Syes.” Moreover, the barbarian origin of some is indicated by their names—Cecrops, Codrus, Aïclus, Cothus, Drymas, and Crinacus. And even to the present day the Thracians, Illyrians, and Epeirotes live on the flanks of the Greeks (though this was still more the case formerly than now); indeed most of the country that at the present time is indisputably Greece is held by the barbarians—Macedonia and certain parts of Thessaly by the Thracians, and the parts above Acarnania and Aetolia by the Thesproti, the Cassopaei, the Amphilochi, the Molossi, and the Athamanes—Epeirotic tribes. (Strabo, Geography LCL 182: 284-285)

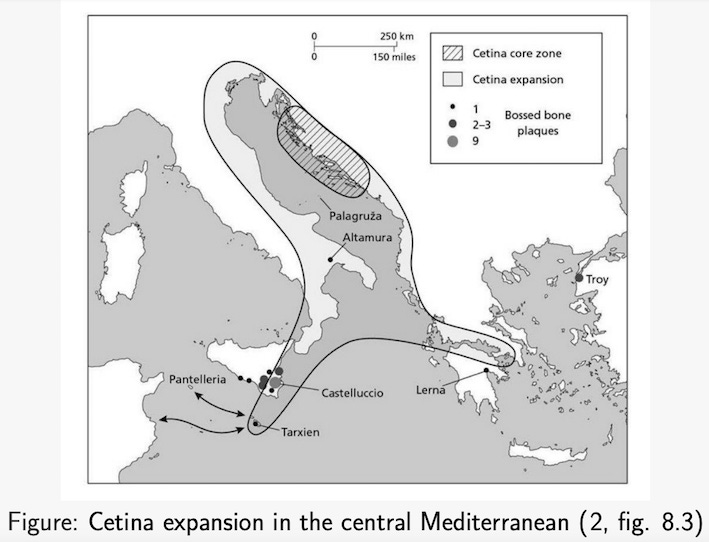

In archaeological literature, migrations into Greece after the period of initial Proto-Greek settlement (ca. 2300-2000 BCE) are well-documented. The areas of origin of these migrations were to the north and east of Greece with different Paleo-Balkan and Anatolian populations settling in Greece. This type of mobility was part of economic (trade), political and cultural networks which connected the region from west Anatolia to the northern Balkans and beyond. Groups and individuals involved in such network often played the role of intermediaries between their area of origin and the trade nodes of the Aegean and the East Mediterranean. One of the archaeological cultural regions which played such a role was Cetina culture, a central Mediterranean group of the final period of the Early Bronze Age which expanded from Dalmatia along & across the Adriatic and the Ionian coast and islands as far as south as the Peloponnese and parts of Attica, Greece.

Patterson et al (2021) and Lazaridis et al (2022) published aDNA samples from major sites of the Cetina culture/phenomenon in the eastern Adriatic. Almost all male samples in the core Cetina area carried hg J2b-L283 in the period 2000-1600 BCE. All of them were descendants of clade Z615, notably Y15058>Z38240 in much of Dalmatia and Z1295>Y21878 in the Velika Gruda tumuli of Montenegro. L283»Z615 has been detected in Shkrel, northern Albania, ca. 1880-1695 BCE (1788 BCE) as this area was a southern extension of Cetina culture. Throughout the Bronze and Iron Ages, the western Balkans are marked by a network of common genetic ancestry.

Current research shows that Cetina groups were strongly interconnected populations where almost all males were descendants of single patrilineages under hg J-L283. Cetina culture was a key part of the west Balkan common ancestry network during its early stages and its diffusion is strongly correlated with the movements of ancestral groups of the Illyrians, as the native peoples of the western Balkans in the Iron Age were collectively known in ancient Greek and Roman literature. The term “Proto-Illyrian” is used to denote the Bronze Age antecedents of the historical Illyrians.

Contemporaneous populations from Albania, the northern Aegean and Dalmatia form a joint cluster, which differs from the southern Aegean regarding Neolithic Caucasus-like gene flow, but also from further inland Balkan in terms of hunter-gatherer ancestry. (Xiaown Jia et al. (2023), Archaeogenomic pilot research of Kamenice, a prehistoric Albanian tumulus 1600-500BCE)

Cetina culture spread in Albania from southern Dalmatia along the Adriatic coast and the Shkodër lakeland was an area of importance for Cetina groups. Further south:

New excavations in the caves of Blazi, Nezir and Keputa indicate that the Ceti-na culture spread in central Albania as well. In fact, several fragments of Cetina ves-sels come from the upper layers of Blazi (under study by M. Gori, T. Krapf). Finally,a handful of Cetina-type sherds and a juglet from Sovjan (Gori 2015, referred to as atankard), a site in the Ohrid-Prespa lakes region, are significant pointers to the im-portance of overland connections in the spread of Cetina features in the south-western Balkans. (Gori, 2018, p. 201)

Cetina groups moved from Montenegro and Albania to southern Greece along the Ionian coast:

The Cetina civilization appeared after the middle of the 3rd millennium (2500-2000 BC) with the area of the homonymous river at the coast of Croatia considered to be its cradle. The description of this culture's people-vehicle as Argonauts of the western Balkans possibly suggests not only the population shifting but also the existence of an active network of contacts in the region where this culture spread.

Typical of the Cetina civilization is the homonymous ware featuring diligent incised and impressed decoration, made of dark clay with burnished surface usually bearing thin incisions densely arranged in various motifs. The dissemination of Cetina ware in a broad geographical region (across the Adriatic sea, up to Malta and the Peloponnese) suggests an already established naval commercial network. This network of contacts or exchanges between the Aegean and the Adriatic sea is not inferred only from the circulation of the particular ware but also from the documented geographical spread of other features of this material culture, such as the clay anchor shaped objects. The people-vehicle of the Cetina civilization seems to have imported ready-made metal objects trading them for their richly decorated ware. Originating in Dalmatia, this ware reached the western Peloponnese (Olympia, Andravida-Lechaina, Nichoria, Teichos Dymaion, Keryneia) and was disseminated further to the east (Lerna). As a consequence, the recovery of this type of poery in Achaea adds to the delineation of a notional arc which, starting at Olympia and passing by Andravida, Teichos Dymaion and Keryneia, ends up in Lerna, thus connecting two sectors of the Peloponnese. (WEST MEDITERRANEAN MUTUAL INFLUENCING IN ART, LIFE AND DEATH in MEDITERRANEAN PATRAS, 2019)

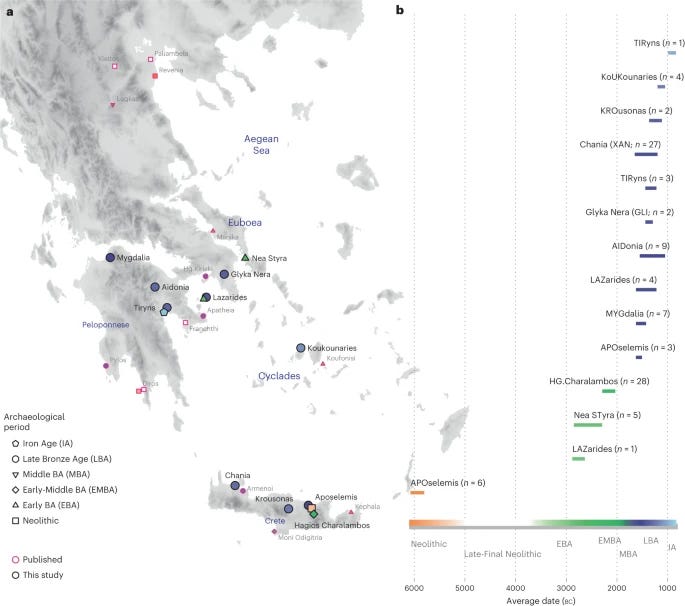

Skourtanioti et al. (2023) analysed genome-wide data from individuals who lived in Bronze Age Greece. One of the sites examined is Mygdalia, a Bronze Age site in Mycenaean Achaea, which was an entry point for Cetina mobility towards the Peloponnese in the pre-Mycenaean era.

The study describes the site as part of a “group of Mycenaean settlements that were founded in the transitional period of Middle Helladic III/Late Helladic I (Mygdalia I) and rose to local prominence in the Early Mycenaean period (Mygdalia II)”.

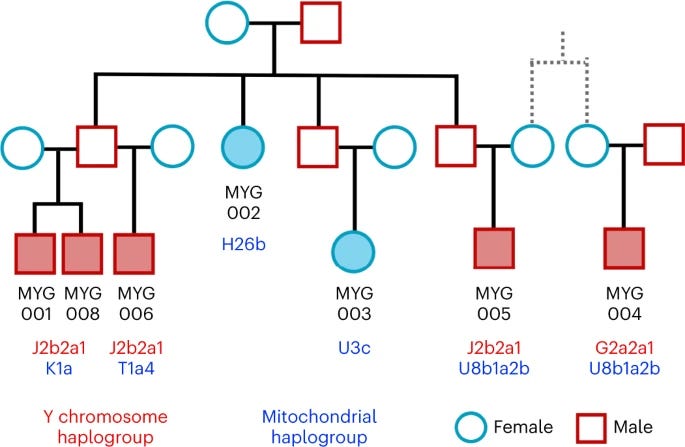

Samples from Mygdalia represent an extended family formed around a single, major patrilineage:

• MYG001 (Intramuros Child Grave3.A) is a perinatal infant of 30-40 weeks in utero with no apparent pathologies. Radiocarbon-dating on human bone (MYG001.A): 3265±21 BP, 1611-1457 cal BC (95% probability), (ID: MAMS-47527, AMS, IntCal20).

• MYG002 (Intramuros Child Grave3.B) is a perinatal infant of 30-40 weeks in utero with no apparent pathologies. Radiocarbon-dating on human bone (MYG002.A): 3318±21 BP, 1626-1518 cal BC (95% probability), (ID: MAMS-47528, AMS, IntCal20).

• MYG003 (Intramuros Child Grave3.C) is an infant of 30-40 weeks in utero with no apparent pathologies. Radiocarbon-dating on human bone (MYG003.A): 3318±21 BP, 1596-1438 cal BC (95% probability), (ID: MAMS-47529, AMS, IntCal20).

• MYG004 (Intramuros Child Grave3.D) is a perinatal infant of 30-40 weeks in utero with no apparent pathologies. Radiocarbon-dating on human bone (MYG004.A): 3318±21 BP, 1609-1446 cal BC (95% probability), (ID: MAMS-47530, AMS, IntCal20).

• MYG005 (Intramuros Child Grave3.E) is a perinatal infant of 30-40 weeks in utero with no apparent pathologies. Radiocarbon-dating on human bone (MYG005.A): 3198±23 BP, 1504-1425 cal BC (95% probability), (ID: MAMS-47531, AMS, IntCal20).

• MYG006 (Intramuros Child Grave3.F) is a perinatal infant of 30-40 weeks in utero with no apparent pathologies. Radiocarbon-dating on human bone (MYG006.A): 3262±29 BP, 1612-1452 cal BC (95% probability), (ID: MAMS-47532, AMS, IntCal20).

• MYG008 (Intramuros Child Grave3.H) is an infant one-three months old with no apparent pathologies. Radiocarbon-dating on human bone (MYG008.A): 3262±29 BP, 1611-1452 cal B-(95% probability), (ID: MAMS-47533, AMS, IntCal20).

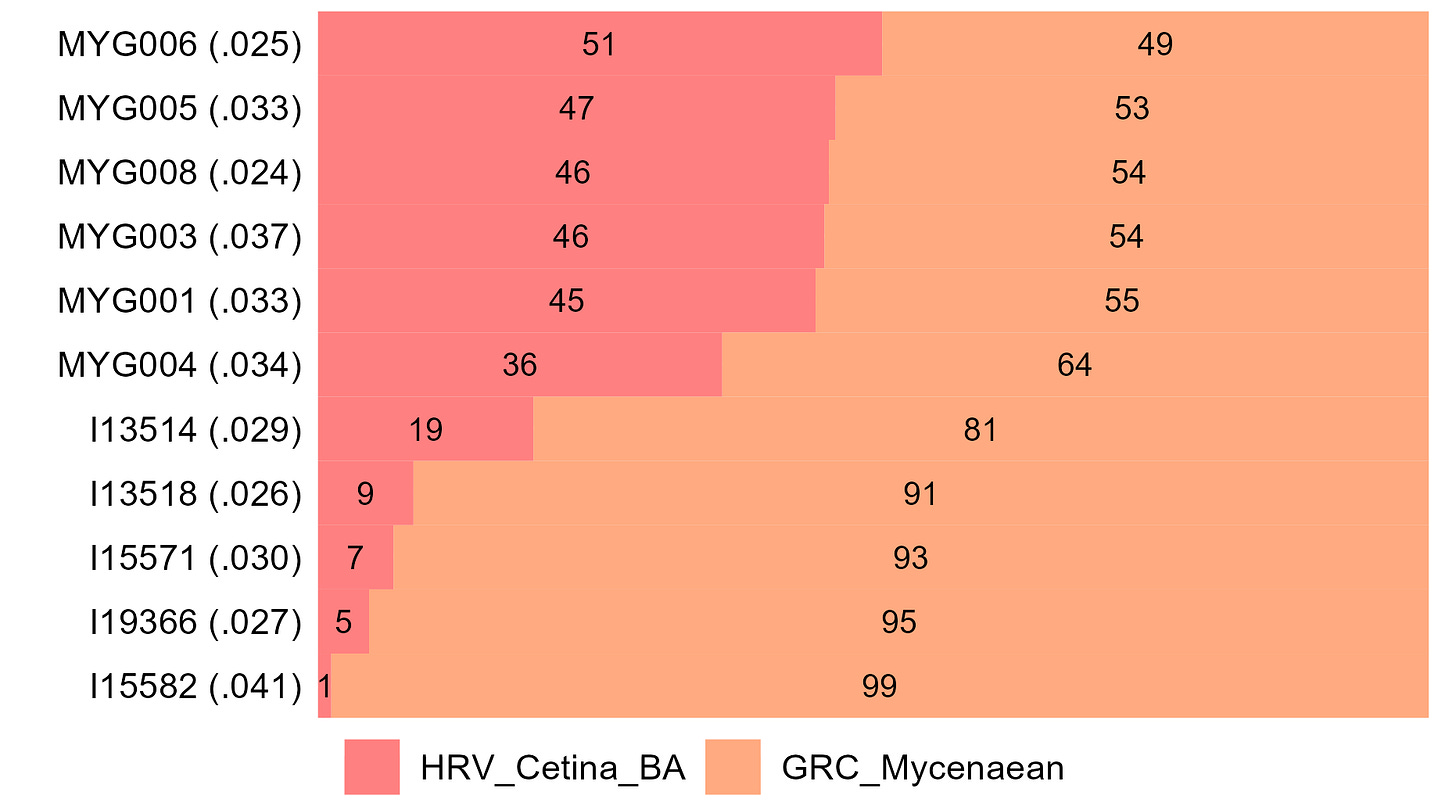

The location of the samples in Achaea overlaps with the areas which had strong interaction with Cetina culture in previous centuries. Most males are patrilineal descendants of a single progenitor. His lineage is J-L283>>Z615. While Z615 was a major patrilineage in the Balkans and the predominant one in Cetina culture, it hasn’t been found yet in any other site older or younger in Greece. Z615 appeared ca. 3000 BCE and the first Z615 samples in Greece appear after the diffusion of the Cetina culture , close to 500 years after the first Z615 were found in Dalmatia. As steppe ancestry was much higher in the Balkans compared to Mycenaean Greece, it is possible to differentiate Cetina-related from Mycenaean-related ancestry. According to Lazaridis et al (2022):

EHG ancestry is ~3-fold lower in the Mycenaean samples than in Bronze Age samples from North Macedonia and Albania immediately to the north of Greece and ~10-fold lower than in Moldova on the edge of the steppe. Thus, our results suggest that although steppe-derived ancestry was present in Bronze Age Greece it was quantitatively the weakest discernible component, only a little above the practically non-existent Balkan hunter-gatherer ancestry.

J-Z2507 has a peri-Adriatic ancient distribution in agreement with the present-day distribution and may represent a Bronze Age or later expansion in the area. The immediately upstream nodes of J-Z2507 are J-Z585, J-Z615, J-Z597 with a similar time depth and include two additional Bronze Age samples from Albania and Croatia, and are thus part of the same pattern.

The difference of the profile in Mygdalia compared to other Mycenaean sites is evident in two-way ancestry models which use Mycenaeans and Cetina culture as their population sources as samples from Mygdalia pick up higher Cetina-related ancestry (close to 50%) in comparison to other Mycenaean samples.

In conclusion, Mygdalia represents the first archaeological site which provides archaeogenetic evidence for Cetina mobility in areas which were part of Mycenaean Greece during the Late Bronze Age. Characterized by high frequency of J-L283»Z615 and higher steppe ancestry than Mycenaeans, samples from Mygdalia provide new insights about the relations of Bronze Age groups from Dalmatia, Montenegro & Albania and the Peloponnese.

Bibliography

Strabo, Geography, Volume III: Books 6-7

Gori, Maja; Recchia, Giulia; Tomas, Helen (2018). "The Cetina phenomenon across the Adriatic during the 2nd half of the 3rd millennium BC: new data and research perspectives". 38° Convegno Nazionale Sulla Preistoria, Protostoria, Storia Della Daunia.

Patterson, N., Isakov, M., Booth, T. et al. "Large-scale migration into Britain during the Middle to Late Bronze Age". Nature (2021). doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04287-4

Lazaridis, I., Alpaslan-Roodenberg, S., Acar, A., Açıkkol, A. et al. (2022). "The genetic history of the Southern Arc: A bridge between West Asia and Europe". Science. 377 (6609): eabm4247. doi:10.1126/science.abm4247

Skourtanioti, E., Ringbauer, H., Gnecchi Ruscone, G., Bianco, R. et al. (2023) "Ancient DNA reveals admixture history and endogamy in the prehistoric Aegean". Nature Ecology and Evolution. 7 (2): 290–303. doi:10.1038/s41559-022-01952-3.