Can Linguistics Provide a Terminus Post Quem for the Albanian Language in Albania?

by Murr Dedi

While the issue of where exactly in the Balkans Proto-Albanian arose and expanded from is still an ongoing debate within academia, in this article we will seek to provide some clarity and insight into the matter, particularly on the question of if linguistics can in fact provide us with a terminus post quem for the presence of Albanians in what is now modern Albania.

As a starting point, we will begin by presenting two examples of Proto-Albanian toponyms attested in Albania prior to the historical attestation of Albanians in the 11th century CE, followed by an analysis of non-Albanian toponymy which further reinforces arguments for an earlier presence of (proto- )Albanian-speakers in the region – placing the terminus post quem in the early centuries of late antiquity in the context of linguistic research.

Mat(i) - a Proto-Albanian hydronym

The hydronym Mat(i), denoting the eponymous river which springs from the mountains of Martanesh and flows through into the lowlands between Lezha and Kurbin before depositing into the Adriatic Sea, offers important insights into the early presence of Proto-Albanianspeakers in Albania. The term mat(i) itself is an Albanian term meaning ‘riverbank, sandy shore’ and is generally accepted in academia to have originated from a Proto-Albanian source, with a potential original meaning of ‘mountain, elevated [place]’ as is suggested by the linguist Vladimir Orel among others.(Orel, 1998, p. 247) Its Indo-European root has been reconstructed as *mn̥-t-. A similar-sounding hydronym is Matoas (likely meaning ‘silty, muddy’) reported by Stephanus of Byzantium as another name for the Danube in addition to Thracian-derived Istros (‘river’) and Danoubis, although it most probably derives from a different IE root to Albanian ‘mat’.(Dyer, 1974, pp. 91-5)

What is perhaps most important regarding Mati for the early history of the Albanians is its date of attestation. The earliest known documentation of the river is found in a text titled De fluminibus, fontibus, lacubus, nemoribus, gentibus, quorum apud poetas mentio fit, authored by a writer known as Vibius Sequester sometime between the late 4th and early 5th centuries CE.(Matzinger, 2009, p. 34) The text served as a list of geographical names supposedly mentioned by renowned Roman poets such as Virgil (ca. 70 – 19 BCE), Ovid (ca. 43 BCE – 17 or 18 CE), Silius (ca. 26 – 101 CE), and Lucan (ca. 39 – 65 CE). Mati is mentioned in the text as a river located between Durrës and Lezhë: Mathis Dyrrachii, non longe a lisso (‘Mati of Durrës, not far from Lezhë), clearly corresponding to the river of the same name in Albania; Mathis representing a literary corruption of Mati. Therefore, by attesting to a Proto-Albanian geographic term, Vibius Sequester’s text establishes a linguistic terminus post quem for the presence of Proto-Albanians in the area around or between the source and mouth of the Mati in north-central Albania, dating back to either the late 300s or early 400s. However, considering that the text purportedly relies on geographic names mentioned by Roman poets living between the first century BCE and the second century CE, the possibility of an earlier origin of the hydronym in the region arises.

The case of Kruja

Another example of an Albanian toponym recorded in Albania prior to the historical attestation of the Albanians is that of Krujë, the renowned mountain settlement situated in north-central Albania. Kruja served as the capital and focal point of the Principality of Arbanon and played a pivotal role as a stronghold of Albanian resistance under Skanderbeg during the Albanian-Ottoman Wars (1432-79 CE).

The toponym itself, derived from the term krua (from Proto-Albanian *krāna), meaning ‘water spring, fountain,’ makes its initial appearance in the historical records in the late 9th century. A certain David of Kruja (Κροιῶν) is noted as among the bishops who attended the Fourth Council of Constantinople held between the years 879 and 880.(Salaville, 1928, p. 410) Subsequently, the toponym is documented a few decades later in the Notitiae episcopatum Ecclesiae Constantinopolitanae, a compilation of ecclesiastical documents from the Patriarchate of Constantinople, presenting lists of various metropolitan and suffragan bishoprics.(Darrouzès, 1981) The Medieval Greek renditions Kroai (Κροαί) and gen. Kroón (Κροῶν) of Krujë/Kruja appear in the Notitia 7, compiled between ca. 901-7 CE by Leo VI the Wise and Patriarch Nicholas Mystikos,(Komatina, 2013, p. 199, 208) designating it as a bishopric of Dyrrachium (Durrës).

Albanian-Slavic linguistic contacts

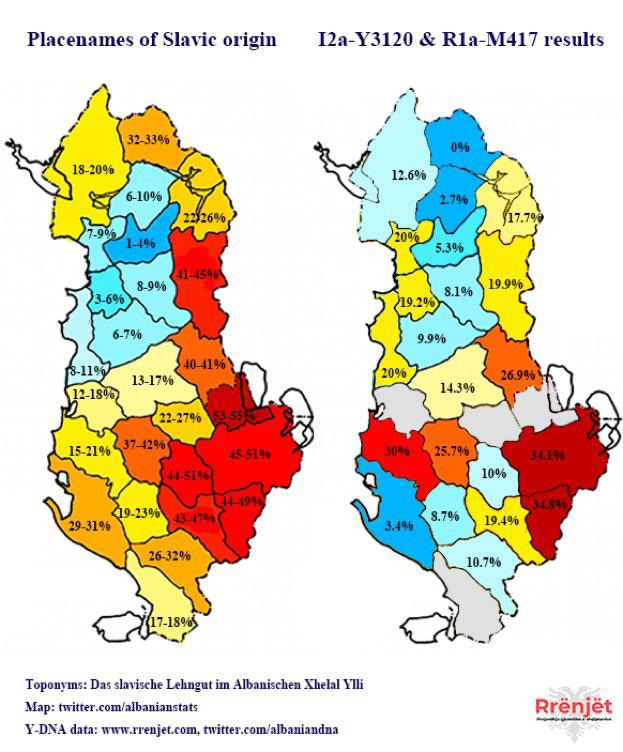

Diverging from the previous two points, our attention will now be directed towards toponyms of non-Albanian origin. As various scholars have already shown, Slavic toponymy can be found across Albania, constituting approximately 24-7% of place names, as suggested by scholars like Xhelal Ylli. Notably, the prevalence of such toponyms reaches its zenith in the south-eastern regions, particularly around Pogradec where they peak at around 53-5%, while the north-central areas exhibit the lowest frequencies, plummeting to only ~1-4% in Mirdita.(Ylli, 2000, p. 198)

While Slavic toponymy as a whole sheds light on the historical interactions between (proto- )Albanian-speakers and the early Slavs of the Balkans, a subset of these place names reflects an earlier phase of assimilation compared to the others. This stratum of toponymy exhibits archaic phonetic features, suggesting, as noted by linguists like Vladimir Orel, that these names were integrated into Albanian between the 6th and 8th centuries CE, coinciding with the earliest period of Slavic settlement and consolidation in the Balkans. Notable phonetic features include the transformation of Old Slavic /s/ into /sh/ and /y/ into /u/ (the same linguistic transformations can be seen in toponyms assimilated into Albanian during antiquity, e.g., Lissus > Lesh > Lezhë). Some of these toponyms, acquired prior to the finalisation of Slavic liquid metathesis, likely date back to before the end of the 8th century.(Ylli, 1997, p. 317)(Orel, 2000, p. 38)

An illustrative example in the north-east is Bushtricë (< *bystrica, ‘swift creek, mountain stream’), situated south of Kukës, showcasing both aforementioned phonetic transformations.(Ylli, 2000, p. 197) This contrasts with Bistricë (e.g., in Delvina) from the same root, acquired during the 800s and onwards as it lacks said features. In the southern part of the country, the toponym Koshovicë (< *kosъ, ‘blackbird,’ with the addition of the Slavic suffix) near the Albanian-Greek border in Dropull serves as another example and contrasts Kosovice.(ibid, p. 130) Other examples include: Shelcan (< *selo, ‘settlement’), Shopël (< *sopъ, ‘hill, hummock,’ alternatively denoting an area where rivers rush through or waterfalls are prevalent),(ibid, pp. 174-5) Ardenicë (likely derived from *ordъ or *ardъ, from which radъ would develop via metathesis, meaning ‘glad, dear,’ and the origin of names with the root Rado/e), and Gërdec (< *gordъ, ‘fortification’).(ibid, p. 267) According to Ylli, phonetic transformations such as /s/ > /sh/ in Slavic toponymy are found most frequently in the former districts of Tropoja, Kukës, and Shkodra in northern Albania. While, Saranda, Kolonja, and Lushnja have the lowest incidences. In the south of the country, the three former districts with highest incidences of this sound transformation are Vlora, Berat, and Fier.(Ylli, 1997, p. 318)

These toponyms serve as clear linguistic evidence of historical contacts between early Albanians and Slavs across Albania during the 500 – 700s CE, and suggests that Albanian and Slavic settlement patterns in the early medieval period should be viewed as more akin to ‘patchwork’ in particular areas, with certain regions showcasing both toponyms that were acquired from Slavic during this earlier phase and those assimilated from the 800s and later. As such, Albanian toponymy of Slavic origin within Albania is the result of linguistic contacts from the far north to the far south in a patchwork pattern in a period which started immediately after Slavic settlement in the Balkans in the 600s.

The case of Durrës

Aside from Slavic toponymy, a noteworthy portion of non-Albanian toponyms in Albania comprises Latin (or Latinised) place names inherited from the Roman period. These toponyms not only affirm the pre-10th century presence of Albanians in Albania but also offer insights into the power dynamics of the Roman Balkans. Before delving into the issues related to this, an examination of the name of the port-city Durrës on Albania’s western coast is warranted. It is unanimously accepted in academia that the city ultimately derives its name from Dyrr(h)achium, the Latinised form of the preceding Ancient Greek Dyrrhachion (Δυρράχιον), which became the official name of the city following its conquest by the Romans in 229 BCE, replacing the more ancient name Epidamnos (Ἐπίδαμνος) in significance.(Demiraj, 2006, p. 126) While many linguists have argued that this toponym was inherited directly from the pre-Slavic era in Albanian, some linguists have argued that the modern Albanian form could not have been directly inherited from Dyrrachium, requiring mediation from another language. According to this argument, Latin /c/ typically produces /q (< k)/ in Albanian, examples including fqinj (< vīcīnus, ‘neighbour’), shoq/shok (< socius, ‘comrade, companion’), and iriq (< ēricius, ‘hedgehog’). Consequently, if Albanian had directly inherited Dyrrachium, it should have resulted in something akin to *Durrëq, as opposed to Durrës, which reflects a /ts/ > /s/ sound transformation.(Matzinger, 2009, p. 26) As such, these scholars (mostly coming from Yugoslav academia) proposed a Slavic mediation theory, suggesting an earlier Slavic form *Dŭràčĭ, which then evolved into Durrës through typical phonetic changes in Albanian.(Çabej, 1985, p. 85) This theory has been dismissed as Latin /c/ had become /tj/ in Late Latin, and accordingly /s/ in Albanian as has been attested in numerous toponyms with Latin suffixes in the Balkans. For example, the Roman historian Eutropius (fl. 363-87 CE) records the Roman city of Viminacium in Moesia Superior as Viminatium. The city is then labelled on the Tabula Peutingeriana, a 13th century map based on an original from late antiquity, as Viminatio. Most importantly, the same map attests to the form Dyrratio (pronounced as /durratso/) for Dyrrachium, thus providing the necessary intermediary form for Durrës.(Demiraj, 2006, pp. 133-4)(Matzinger, 2021, p. 132)

Linguists like Matzinger (a former proponent of the Slavic intermediary argument) have argued that this palatalised Late Latin form gave rise to the Proto-Albanian toponym around the 5th century or soon after.(Matzinger, 2009, p. 27) However, this seems arbitrary since the transformation of /c/ > /tj/ is recorded by Eutropius, a historian writing during the 4th century, and the timeframe for Late Latin linguistic developments is placed between the 3rd and 6th centuries CE. As will be explained further, the assimilation of this toponym from a Latin source does not necessarily mean that the Proto-Albanians were entirely unaware or had not known of the toponym beforehand, or that they were recent arrivals in the area. This is especially suggested by the fact that, as analysed above, Mati is recorded as an established hydronym by the 4th – 5 th century. To suggest that Proto-Albanians had been present in this region but not around Durrës just to the west until the 3rd – 6th century, especially considering the explicit connection between the river and the city in the eyes of writers from antiquity, is an unreasonable assumption devoid of any argumentation which takes into account the geographical context of the region.

Albanian-Latin linguistic contacts

As noted above, it must be borne in mind that toponymy can (and does) reflect historical power dynamics. In the Roman Balkans, in all regions at least two languages co-existed: Latin as the official language, and at least one of the languages spoken by the pre-Roman locals. Toponymy itself reflects this geo-linguistic dualism, as is evidenced by the presence of both pre-Roman and Latin place names in Albania.The ratio of Latin to non-Latin toponyms does not necessarily reflect demographic shifts or Romanisation processes. Language expression in public space in the form of inscription or textual production is itself a process of linguistic hierarchies and power imbalances. Simply put, Latin as the official language of the empire had a higher status than the local languages. As such, Latin toponyms or the Latinised forms of local toponyms may have held a higher status even among locals compared to their non-Latin predecessors, and thus may have replaced them. The replacement of local toponyms by ‘foreign’ toponyms in the language spoken by the locals of a region is not a phenomenon unique to Albanian, but a universal aspect of the fact that language use is not neutral but reflects power relations. The small Greek island of Megisti off the coast of modern Turkey came to be controlled by the Knights Hospitaller in the Middle Ages and soon the island came to be known even among the Greek-speaking locals as Kastellorizo (< Castellorizo), a toponym derived from Italian. The locals of the island were Greek-speakers and remained so, but the toponym changed without any western European colonisation of the island or the replacement of the indigenous population. The same phenomenon is still ongoing in Albanian. Older toponyms of Italian cities like Trieshtë have been replaced by toponyms which reflect modern Italian pronunciation (Trieste).

In the case of Proto-Albanian and Latin, the hydronym Shkumbin, the river which flows from the mountains of Valamara and into the Adriatic, is derived from Latin Scampinus (Matzinger’s theory of Slavic mediation is unnecessary and unsubstantiated) which replaced the native Illyrian name Genusus (derived by some from *g’enu, ‘knee,’ in turn connecting it to Albanian gju).(Demiraj, 2006, p. 150)(Matzinger, 2015, p. 62) These power dynamics makes it so that the linguistic origins of certain toponyms from Latin cannot be interpreted simply as the result of Romanisation or replacement of the locals. In the Balkans this trend can also been seen with place names introduced during the Ottoman period, an example being that of Kyustendil (Кюстендил) in western Bulgaria. The toponym is derived from Kösten, a Turkish variation of the Latin anthroponym Constans, with the addition of the Turkish suffix - dil; named after the former Serbian ruler of this area, Konstantin Dejanović (r. 1378-95 CE). During antiquity the settlement was known as Pautalia which later became Velbazhd following Slavic settlement and consolidation in the region during the medieval period. With the change from Velbazhd into Kyustendil, we see a shift despite no process of Turkification of the locals, thus simply depicting a power dynamic.

It is also important to note that there appears to have been a great degree of (proto- )Albanian-Latin linguistic symbiosis and, most likely, bilingualism. On top of the vast number of Latin loanwords in Albanian, there are clear examples of Albanian place names which contain an Albanian root or prefix and a Latin suffix. Such examples include those with the suffix -et from Latin -ētum: Shkozët (< shkozë, ‘hornbeam’) and Shpërdhet (< shpardh, ‘Hungarian/Italian oak’).(Bonnet, 1998, p. 323) As such, not only was Albanian influenced by Latin, but local Latin was in fact spoken by Albanian-speakers and in turn symbiotic Albanian-Latin toponyms were formed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the hydronym Mati, with its Proto-Albanian roots, attested as early as the late 4th to early 5th centuries, establishes a firm historical footprint for Proto-Albanians in north-central Albania during late antiquity. Through the thorough examination of toponymy in Albania, it becomes abundantly clear that the linguistic ancestors of the Albanians could not have arrived in Albania as late as the 9th century CE or any era which post-dates antiquity. Similarly, the toponym Krujë, documented in the late 9th century, also challenges this claim on the same grounds. Slavic toponymy on the other hand, reveals historical contacts between early Albanians and Slavs across Albania during the 6th and 8 th centuries, while certain Latin place names showcase assimilation between the 3rd and 6th centuries. These linguistic interactions underscore the historical tapestry of Albania, emphasising the enduring presence and dynamic linguistic development of the Albanian language and its native speakers in the region from antiquity to the modern era. Linguistic evidence from Albanian and the contact of Albanian with other languages like Latin and Slavic place Albanian firmly in Albania and the surrounding regions in late antiquity. The connection of Albanian to pre-Latin toponyms like Dimal and tribal names such as that of the Taulantii provide a framework for the location of Pre-Proto-Albanian among the southern Illyro-Messapic dialects located in Albania and neighbouring areas. This connection will be explored in full in future articles.

Bibliography

1) Bonnet, G; Les mots latins de l’albanais (1998)

2) Darrouzès, J; Notitiae episcopatuum Ecclesiae Constantinopolitanae (1981)

3) Demiraj, S; The Origin of the Albanians: Linguistically Investigated (2006)

4) Dyer, R; ‘Matoas, the Thraco-Phrygian name for the Danube, and the IE root *madų’, Glotta 52.1/2 (1974), pp. 91-5

5) Çabej, E; ‘The problem of the place of formation of the Albanian language’, in The Albanians and their Territories (1985), pp. 63-100

6) Komatina, P; ‘Date of the Composition of the Notitiae episcopatuum ecclesiae Constantinopolitanae nos 4, 5 and 6’, Zbornik radova Vizantoloskog instituta 50.1 (2013), pp. 195-214

7) Lippert, A., Matzinger, J; Die Illyrer: Gescichte, Archäologie, und Sprache (2021)

8) Matzinger, J; ‘Shqiptarët si pasardhës të ilirëve nga këndvështrimi i gjuhësisë historike’, in Historia e Shqiptarëve: Gjendja dhe perspektivat e studimeve (2009), pp. 13-39

9) Matzinger, J; ‘Messapico e Illirico’, L’Idomeno 19 (2015), pp. 57-66

10) Orel, V; Albanian Etymological Dictionary (1998)

11) Orel, V; A Concise Historical Grammar of the Albanian Language: Reconstruction of ProtoAlbanian (2000)

12) Salaville, S; ‘Épitaphe métrique de Constantin Mélès, archidiacre d’Arbanon († début du XIIIe siècle ou fin du XIIe)’, Revue des études byzantines 152 (1928), pp. 403-16

13) Ylli, X; Das slavische Lehngut im Albanischen, Teil 1: Lehnwörter (1997)

14) Ylli, X; Das slavische Lehngut im Albanischen, Teil 2: Ortsnamen (2000)